Assessing the Needs of the World’s Most Food Insecure Countries

In the above image, enumerators and residents in the northwest of the Syrian Arab Republic assess the damage to solar energy infrastructure and buildings following the devastating earthquakes in Turkey. ©FAO

Analysts at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) use GIS, remote sensing, and survey data to evaluate food security and agricultural production to make countries prone to multiple shocks more resilient to disruptions. (Editor’s note: The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.)

Key Takeaways

- FAO analysts gather data to analyze drivers of food insecurity in countries that experience ongoing food crises.

- Enumerators conduct surveys with agricultural and non-agricultural households to understand the state of income and shocks, crops, livestock, food security, and needs.

- The Data in Emergencies (DIEM) Hub provides open access to all data collected and in-depth reports.

In 2022, it was the onset of the ongoing conflict in Ukraine. In 2023, it was extreme heat across many countries and fall armyworms munching maize crops across southern Africa. These leading causes of food insecurity are just a few of the crises in focus for the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The Data in Emergencies (DIEM) team uses satellite imagery, data collected from the field, and advanced spatial analysis and mapping to investigate root causes and mitigation strategies to reduce food insecurity.

“People are living in situations where they are constantly being hit by something,” said Neil Marsland, head of the DIEM team in the Office of Emergencies and Resilience at FAO in Rome. “You can have a flood followed by a livestock disease outbreak and, at the same time, have conflict breaking out and the currency plunging.”

FAO kicked off a data-driven monitoring program in 2020—during the pandemic—to assess rising agricultural stresses in countries where food insecurity has become chronic. To monitor food vulnerability and survey the needs of farmers, the team created the DIEM Hub using geographic information system (GIS) technology and remote sensing.

Food scarcity has historically been connected to government instability. According to the World Food Programme, more than 80 per cent of UN mobilized resources have gone to conflict areas in recent years. The most war-torn countries face perpetual cycles of hunger and instability.

“Famines are pretty rare, thankfully, but we do have many situations where people are rapidly depleting their assets to get access to food,” Marsland said. “They’re engaging in what we call negative coping strategies, such as selling off their last productive animal or migrating away from the household in a desperate attempt to find work.”

Working Where the Need Is Greatest

Marsland and the DIEM team monitor 27 countries facing food crises and analyze the connections among climate change, conflict, migration, geopolitics, and economics. Analysts on the team used satellite imagery and GIS technology to create models that can detect livestock hardship and crop stress. Inputs from a network of in-country enumerators add perspective on agricultural production and the impact of storms or pests, helping the team determine what producers may need. When it’s too dangerous to go door-to-door, assessments are completed via computer-assisted telephone interviews.

“They’re telling us they need food, but also other things,” Marsland said. “They need seed to plant the next crop and vaccinations to keep their animals from dying. With GIS, we’re able to map and display this data very clearly. We can compare needs within a country, across time, and look at the needs of all countries.”

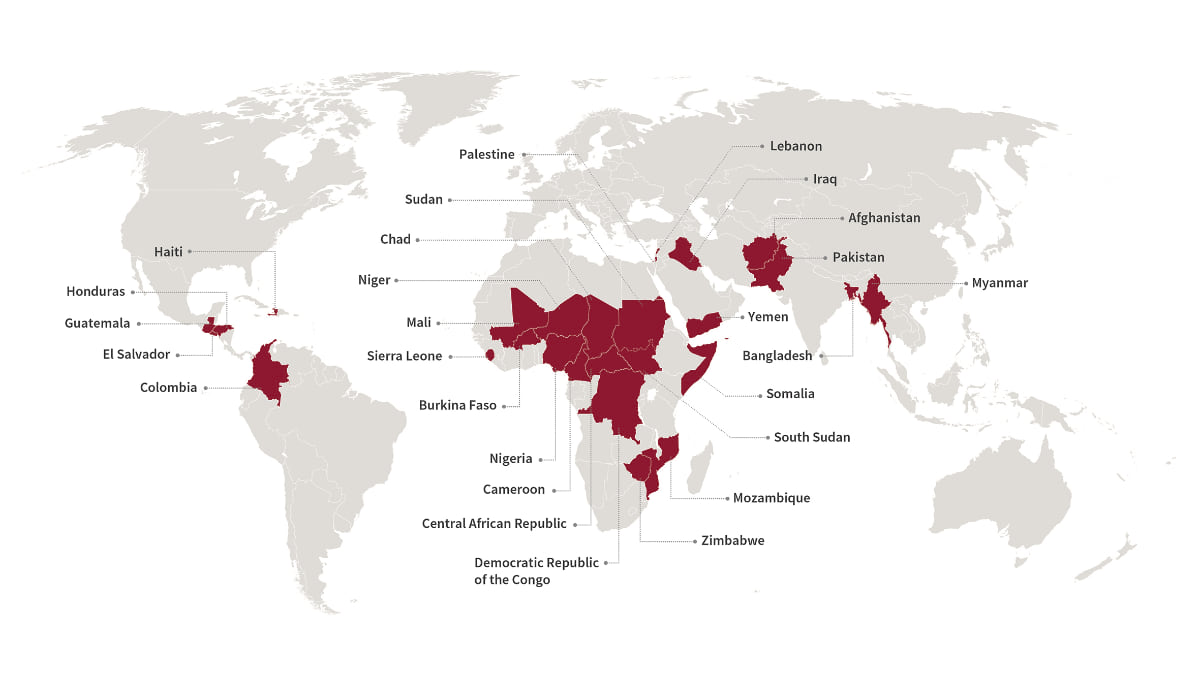

The number of hungry and malnourished people in the world had been declining before it began rising in 2016. The setback came with an increase in extreme storms and conflicts. This map shows the 27 countries the DIEM Information System monitors. ©FAO

The number of hungry and malnourished people in the world had been declining before it began rising in 2016. The setback came with an increase in extreme storms and conflicts. This map shows the 27 countries the DIEM Information System monitors. ©FAO

The DIEM Hub analyzes, maps, and stores the 150 indicators collected during each survey in countries such as Afghanistan, Lebanon, Yemen, Burkina Faso, Mali, Sudan, and Colombia. The surveys of approximately 150,000 households each year—performed every two to six months—provide an accurate picture of food production trends and volatilities.

Since the DIEM Information System was launched, the team has extended its network of partners, including national government agencies in the countries it monitors.

Prior to 2020, the UN did not receive regular updates on how and where food-insecure regions were impacted by crises. Now, through DIEM’s DIEM-Impact, analysts can provide initial impact assessments within 72 hours of a shock or hazard. This has been helpful in understanding events such as the flooding in Libya, the destruction of the Kakhovka dam in Ukraine, tropical cyclone Mocha in Myanmar, and the fall armyworm infestation in Burkina Faso. These reports, often built with ArcGIS StoryMaps, present compelling and actionable details.

Survey apps on mobile phones help streamline data collection. Automation and cloud computing enable rapid data processing. Digital workflows validate data and speed government approvals. And the DIEM Hub, an open data site, shares information and stories instantly.

After consecutive earthquakes hit Afghanistan in early October 2023, the DIEM team analyzed satellite images to assess the impact on agriculture and livelihoods. ©FAO

After consecutive earthquakes hit Afghanistan in early October 2023, the DIEM team analyzed satellite images to assess the impact on agriculture and livelihoods. ©FAO

Analyzing Cascading Impacts of Conflict

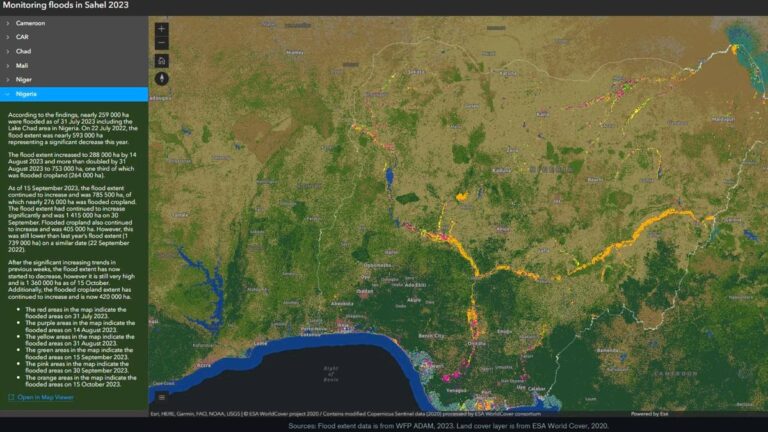

The DIEM Information System has evolved over the few years it has been operating. Analysis conducted in the Sahel region of West Africa helped transform the team’s mission when they were able to provide accurate data and quantify the complex factors leading to food insecurity across the region—extending beyond monitoring to show causes and effects.

“We’ve been able to analyze ongoing conflict in the Sahel and the impact of seasonal flooding that has become more frequent and severe with climate change,” Marsland said. “We provide a really good set of tools to analyze the impacts affecting marginalized individuals and communities that depend on growing crops and taking care of livestock.”

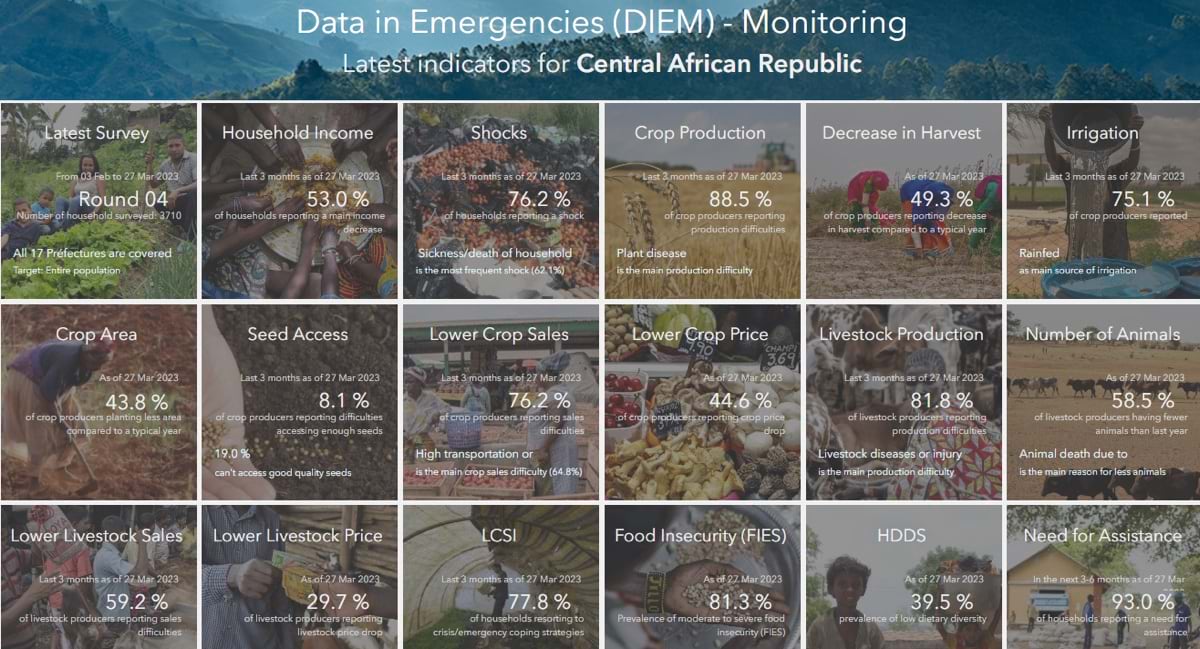

In the Central African Republic, a 2013 coup led to ongoing waves of internal armed conflict, forcing people to flee and disrupting agricultural production. According to the World Food Programme, over one million people (one in four residents) now live in refugee camps or shelters in neighbouring countries.

In the Central African Republic, a 2013 coup led to ongoing waves of internal armed conflict, forcing people to flee and disrupting agricultural production. According to the World Food Programme, over one million people (one in four residents) now live in refugee camps or shelters in neighbouring countries.

Reports include analysis of satellite images, including radar images to see through clouds, and all the local knowledge the team collects about agricultural conditions and impacts.

When Ukraine’s Kakhovka dam was breached, for instance, the immediate concern was that the nearby farms would be flooded. But then analysts began to look more closely at the effects of the emptying reservoir.

“We realized the main problem was the irrigation channels,” said Andrea Amparore, data manager for DIEM. “There are three irrigation systems—among the biggest in the world—that were fed by the reservoir. The loss of water will have a huge impact on agricultural production in Ukraine and Russian-occupied territories until the dam can be rebuilt.”

Knowing the food-related impacts on people helps the network of providers prioritize relief work and devise longer-term strategies—such as determining how to fill the gap in grain caused by the ongoing conflict in Ukraine.

Expanding the Reach

Analysts at Cornell University and local universities such as Marondera University in Zimbabwe also use the data stored in the DIEM Hub to examine root causes of food insecurity and to come up with strategies to mitigate hunger.

“Professors and their students investigate possible connections between shocks and food insecurities,” Amparore said. “They explore the factors that can increase or decrease the resilience of certain households compared to others.”

To further extend analytical capabilities, the DIEM team is investigating how artificial-intelligence-based machine learning can process imagery and further automate answers to questions.

While only a few years old, DIEM has gained momentum and a growing appreciation from the community of food providers it serves. The work recently appeared in the world’s leading multidisciplinary science journal Nature. The team has visits planned to the various DIEM regions to build awareness of the available data and encourage local investment in the initiative.

In its ongoing work, DIEM will continue to build awareness of the tool to support sustainable and sustained food monitoring. The ultimate goal is to foster stability in the countries prone to multiple shocks.

“What we hear in the headlines is people being given emergency food, which is clearly a critical intervention,” Marsland said. “What we’re trying to understand in more detail is what other needs these households have to support their livelihoods and their families—and as importantly, what to do about it.”